the advances and retreats in the battle

to make children’s books more inclusive and diverse

IBBY Belonging Conference 2014

Most of the books we had were imported from England, so my reading was peopled with girls called Hilary, Gwendolin, Pamela and Penelope (I’d never heard this name spoken aloud and in my head she was always Pee-ne-pole!).

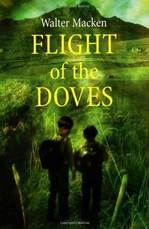

| Then someone gave me Walter Macken’s Flight of the Doves. I will never forget it. Two young children run away from an abusive step-father in London to try to find their granny in Galway. I so remember when I came to that bit – I’d heard of Galway – in fact I’d even been there! Suddenly, the book felt real rather than just the wonderful imaginative escape it had been up to then. Someone like me (who said Mammy, and strand and briars…) was in a book! |

This was the late 1980s, years before Ireland’s Celtic Tiger and so, like a quarter of a million other young people leaving the country every year I became an economic migrant, leaving for England in 1988.

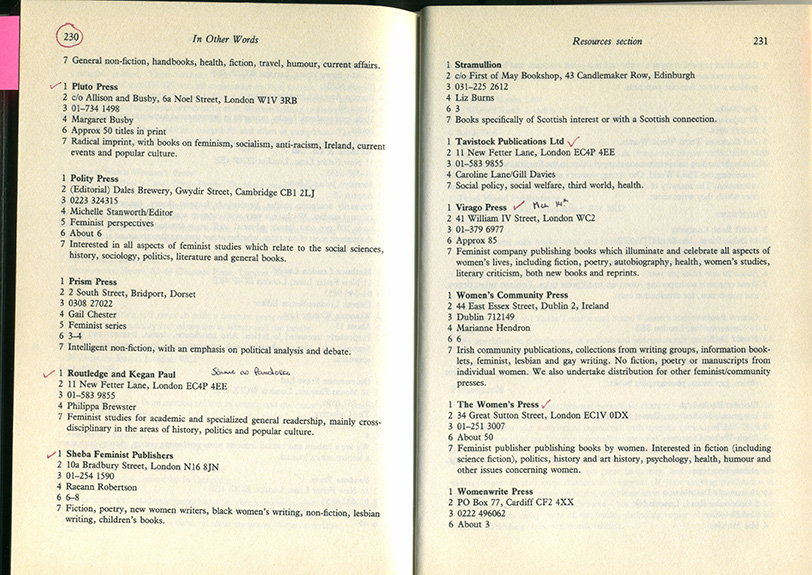

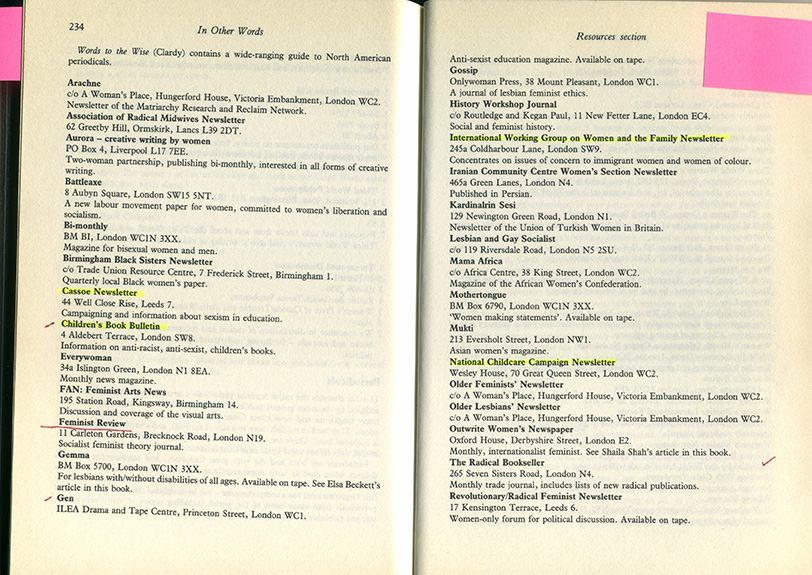

The first thing I joined was Woman in Publishing – in those days, we couldn’t search the internet, and WiP had an extremely useful directory, ran courses and other events to help women in publishing to network and progress. I also bought Rolling their Own and In other Words.

What amazes me now, looking at these, is the amount of feminist publishers and magazines and pamphleteers there were (including the wonderful Older Feminists’ Newsletter and the Older Lesbians’ Newsletter – there’s one for all the 20 somethings who think they invented feminism!!) I know some have been replaced with blogs and other internet forums, but sadly, many have gone…

In fact, it was my teaching qualifications and experience that got me my first job – as an editor with NFER-Nelson (where I worked for two years and edited the UK’s first SATs). I felt that if I got some solid editorial experience, I could then do another round of applications…

1990

Letterbox Library Conference –

Equality and Diversity in Children's Books

Then came my Damascus moment. I don’t quite know how I came to hear about it, but I went to a Letterbox conference.

And so began a course of reading which brought together my two passions: child development and politics.

| I started with Untying the Apron Strings edited by Naima Browne & Pauline France OUP, first published in 1986. It presented arguments and research to challenge ideas of biological determinism, quoting from Archer 1978, Griffiths and Saraga 1979, Bland 1981, Maccoby and Jackline 1974, and Fairweather in 1976. Looking at them again now, I particularly love the comment on page 52: ‘given the theoretical criticisms of biological explanations it is surprising to find so many people still continuing to promote such ideas.’ (my italics – this was in 1986!). In Other Words - Writing as a feminist edited by Gail Chester and Sigrid Nielsen (Hutchinson) 1986 was also a huge influence. Caroline Halliday’s chapter – I tell my 3 year old she’s real… writing lesbian-feminist children’s books was particularly influential. |

| "Reading a bedtime story is not as calm as it used to be. Not if you are a lesbian mother with a daughter who as a disability. A child needs to find her/his self, her likeness in the books she uses, not some patriarchal notion of the ‘normal’ child…Writing for children in this context demands thinking out and expressing the most exciting politics I can manage, to present positive and accurate images of children and adults with disabilities… and at the same time reduce the racism and class stereotypes." |

She went on to say, ‘Feminist children’s books must show the multiracial society in this country, in which children and woman live in different classes and are affected by race and class divisions. The books must explain how people live in different ways here and all over the world…’

This challenged my thinking. I regarded myself as someone whose feminist politics fed a desire for equality across class and race, but I had not given as much thought to the effect of stereotypical images on the development of young Black children as I had, for example, thought about their impact on young girls.

| So began another tranche of reading. Reading Into Racism – bias in children’s literature and learning materials by Gillian Klein (Routledge 1985) being first among the books I devoured. Klein presented evidence from studies that showed that providing Black children with positive role models (both real people and in books) led to a positive shift in self -image. She also describes how Black children were quite capable of reading but had little motivation to read when they didn’t see themselves or their experiences reflected in the books they used. Klein helpfully provides references to resources, reports and articles for teachers by ILEA, CRE and NUT. |

But they also highlighted the dearth of material available and, with others, set about improving the supply and creating demand. Klien notes that Judith Elkin ‘had far more to choose from in her 1983 series of six articles for the journal Books for Keeps: ‘Multicultural books for children’.

This groundswell of research, consciousness raising and demand for better material was garnering a positive response. Publishers like Frances Lincoln, A&C Black, Gollancz, Magi, Soma, Tamarind and Child’s Play published strongly diverse lists and even mainstream publishers like Penguin and Puffin made a real effort, as described in Books for Keeps. In September 1988, their News section celebrated Puffin’s ‘three new booklists’: Equality Street (multi-cultural listings); Ms Muffet Fights Back (non-sexist listings) both compiled by Susan Adler, an Equal Opportunities Librarian, and Special Needs (compiled by Beverley Mathias, Director of the National Library for the Handicapped Child). These were listings (under the three headings) of books published or about to be published by Puffin.

I was lucky to be part of this wonderful momentum as I got my first job in children’s publishing in Child’s Play at the end of 1991.

1991

In 1991, also following that life-changing Letterbox conference, I joined The Working Group Against Racism in Children’s Resources. Sitting alongside Verna Wilkins, Nandini Mane, Abiola Ogunsola, Steph Smith, Eileen Brown, Asha Kathoria, Rita Mitchell, Lorna Stoddart, Robert Roach and Felicity Weitzel (among so many others who gave of their time) I learned so much.

1993

Guidelines and Selected Titles 100 Picture Books

chosen by the Working Group Against Racism in Children's Resources

In 1992, we came to the conclusion that, in addition to campaigning against racism (Little Black Sambo was still widely distributed at the time), the time had come to celebrate publishers who were producing books we would be happy to promote to schools and libraries. We set about producing Guidelines and Selected Titles and were thrilled to hit a magic 100 books we were happy to stand by.

| The introduction to our publication in 1993 pulled together some of the research and arguments for the importance of inclusive non-biased books for children; we included the criteria we had used; and included a checklist which had developed out of our reviewing so teachers and librarians could use it for future reviews. We were disappointed that so many of the books were American imports, but felt happy that the momentum was moving in a positive direction. The publication was a great success. It pulled together in one place what was available, and teachers and librarians could be confident that the selected books had been vetted by a diverse group. |

Between 1991 and 2002 my own working life had also been moving forward. I had freelanced for Verna Wilkins at Tamarind, worked at Victoria House Publishing in Bath, at Readers Digest and at Frances Lincoln. In 1995 I was asked to start a new list for DeAgostini Editions and it was wonderful to be able to start a fresh list that I hoped could be inclusive from the beginning.

The Sales Director and I did a management buy-out in 1997 (a learning experience in itself) and started Zero to Ten publishing, which in turn was bought by Evans Brothers.

In 2002 I was made redundant and in 2004 started my own small imprint Alanna Books.

2004

Cultural Diversity & Publishing is in the news

| 2004 saw another resurgence of focus on the lack of diversity in publishing. The Bookseller magazine in association with the Arts Council of England and decibel carried out a survey and published the results in a report called In Full Colour -Cultural Diversity in Book Publishing Today. Nicholas Clee introduced the report with a leader called Diversity makes business sense. He argued that ‘the moral arguments for cultural diversity are backed by strong economic incentives’ pointing out that the advertising industry estimates that ‘Black and Asian communities have an annual disposal income of £32bn.’ |

It seemed that we’d won the moral arguments and now the commercial ones too - it kicked into touch any counter arguments that diversity was a ‘nice to have’ luxury.

A less rosy picture was painted by Are you simpatico? by Benedicte Page. In it, Andrea Levy argued that despite successes of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Monica Ali’s Brick Lane, ‘Black writers need to be better than their white counterparts to be accepted for publication.” The article also bemoaned the fact that publishers are happier with novels that deal with issues of race, effectively ghettoizing writers.

The Bookseller report was followed swiftly by the launch of the Diversity in Publishing Network (DipNet) to tackle the issues raised by the report.

2006

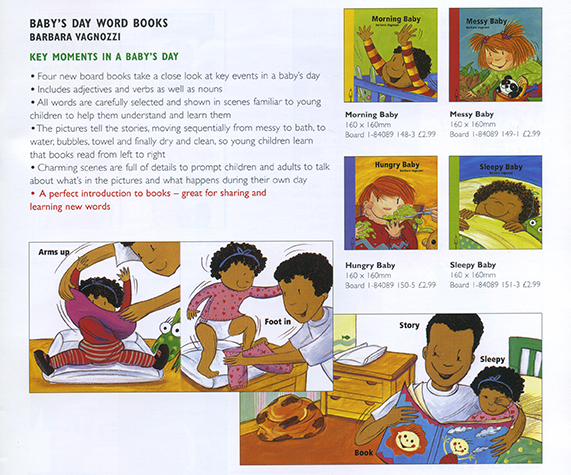

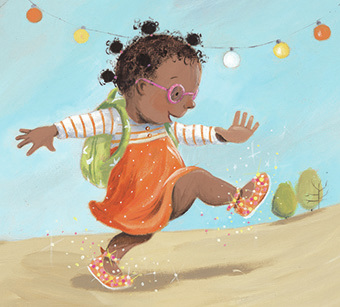

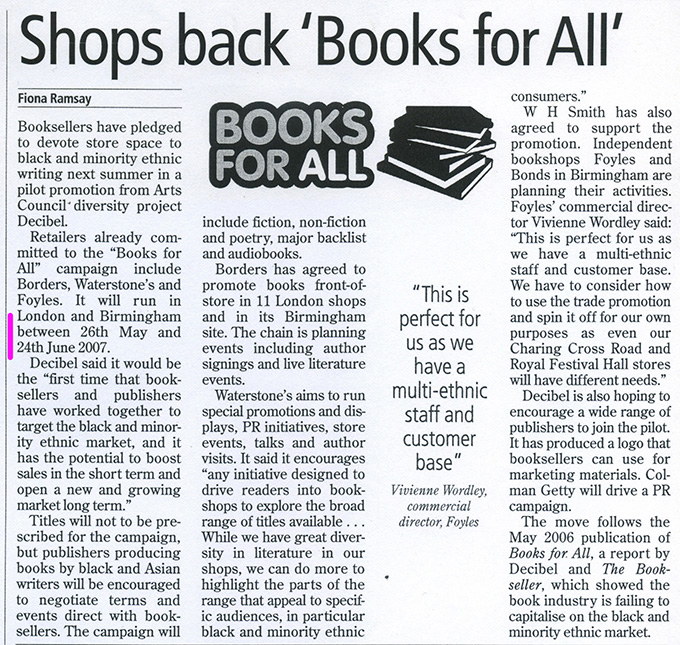

| March 2006 saw the launch of my first title as Alanna Books (a small inclusive list launched by a small Black Girl called Lulu. The timing seemed perfect – for, shortly afterwards the Bookseller had another report, this time focusing specifically on children’s publishing called, Books for All Diversity matters: growing markets in children’s publishing. |

In Challenge of the culture club Verna Wilkins of Tamarind said the difficulty was not in teaching Black and other minority ethnic children to read, but in getting them to continue to read when ‘they cannot identify with the material they are presented with, or because the book’s context and curriculum exclude them’. While this was not news to those of us actively campaigning in the area, it was progress to see it in a mainstream trade journal.

Verna Wilkins also spoke about the dozens of manuscripts submitted to her publishing company by parents telling her that ‘they haven’t found suitable books, so they have attempted to write some themselves.’ This issue of demand outstripping supply was also raised in Young and Demanding.

In fact Jenny Morris owner of the Lion and the Unicorn bookshop said ‘the interest in publishing that kind of book for the general consumer market has almost disappeared’ naming ‘a few brave publishers such as Frances Lincoln’ as continuing to publish culturally diverse books.

I remember reading this in disbelief – 25 years on from the librarians Janet Hill and Judith Elkin first raised the issue of demand outstripping supply and a) we’re still here and b) it seems we’d already peaked and I’d missed it!

What was positive was development and growing maturity of that demand. It seemed to me that not only was demand outstripping supply, but that young readers were looking for a more complex, nuanced, mature and sophisticated read than what was on offer.

Young teenagers (themselves growing up in diverse classrooms) who were interviewed by the report bemoaned the mono-ethnic approach of books that focused on one race or culture. As one teen eloquently put it, ‘we’re not integrated enough in books – publishers aren’t letting us mix in.’

Literary agent, Jennifer Luithlen, spoke highly of Bali Rai’s work as appealing not just to Asian children but to all British teenagers. Another teen in The culturally diverse young article added, ‘the reason why people don’t want to read ethnic writers is because they think they’re going to drone on about racism’ echoing the comments in the previous report by Benedicte Page about publishers expectations that BME writers should only write about BME issues.

So, while I was disappointed at the need to restate some, by now, very old arguments, I was VERY excited that the book industry seemed to be accepting the commercial as well as the moral arguments for inclusion and taking positive, practical actions. It seemed to me that the Books for All campaign was limited in its one-month duration, but it was hoped that this would be a pilot for future initiatives.

I was also excited that the demand of readers was growing and maturing – it seemed to me that important as consciousness-raising was, there was a growing appetite for books which were what I would call naturally diverse and inclusive; which were not about race or focused on minority issues but rather had regular stories which just happened to feature a BME character or family. For me, it had always been important that BME children (and girls and LGBT characters and those with disabilities) had a right to be in any story (and to be the hero).

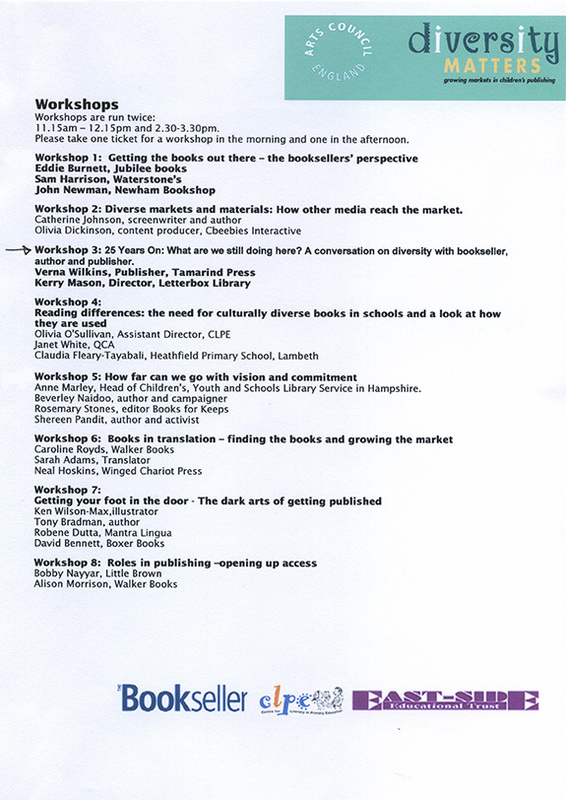

Then in June 2006 the Arts Council organized the Diversity Matters conference.

| There were talks and panel discussions and workshops including one, ironically called 25 Years On: What are we still doing here? A conversation on diversity with author and publisher Verna Wilkins of Tamarind and bookseller Kerry Mason of Letterbox. For, welcome though the conference was, it was 15 years since that Letterbox conference in 1991, and over 30 years since those demands from the two heroic librarians. It was valid to ask why were we still having the same discussions… |

Of course it’s not wrong to have this discussion, in fact, sadly, it is very necessary. But my question to you is - What can we do to make sure we’re NOT having the same debate in 2024?

I have some suggestions:

First, know your history

We have been fighting for the right of children to see themselves in books and so feel that they belong since at least the 1970s. We’ve done the research and…

• we already know babies are aware of and negatively affected by bias from as early as 18 months;

• we already know that not seeing themselves in literature negatively effects children’s motivation to read and learn, their self esteem and their mental health;

• we already know that narrow ‘norms’ offered in literature also damage ‘non minority’ children, limiting their dreams, imaginations and their capacity for empathy and understanding;

• we already know that publishers are not ‘charities’ and cannot publish uncommercial titles however worthy but we also know that demand continues to outstrip supply and that there are lots of customers for inclusive books;

• we already know that the argument that books with pink glittery (able-bodied, white, straight) princesses / blue macho (able-bodied, white, straight) heroes is “just what children want” is spurious;

• we already know that we’re not asking for bland, politically-correct, inoffensive stories about beige children set in some ‘ideal world’ in grey covers;

• we already know that we just want books that have a range of characters that reflect the real diverse world we live in;

There have been volumes and volumes of studies and reports and articles and books and blogs explaining and defending and proving over and over and over and over and over…

So I think we can safely stop explaining and arguing and defending and proving…

We already know!

We need to act!

We cannot allow children's reading, development, imaginations and dreams to be limited by narrow revenue categories however convenient and successful they are for retailers. While the industry regards inclusive or diverse books as not commercial they are pushed off the shelf by the ‘easy sell' of pink glitter / adventure stories. So, while ours might be a political campaign, it is fought in a commercial arena and money talks...

This was brought home to me last year by the storm which erupted over The Independent’s book reviewer Katy Guest’s decision to no longer review books which had ‘for boys’ or ‘for girls’ in the title (this was in support of the Let Books be Books campaign). Wow was she attacked! Scrolling through comments, what saddened me (aside from the violent nature of the attacks) was the amount of energy and space and time people spent defending the need to for diversity, arguing about biological determinism… I though, ‘you know, we don’t need to do this… we already know…’

(What I did suggest was that to counter all those who threatened to never buy the Independent again, anyone supporting Katy should not limit themselves to tweeting support, but should go out and buy the Independent that Sunday – buy two copies! You can read my blog about it on http://www.annamcquinn.com/blog/heads-above-the-parapet). I felt we needed to put our money where our mouths were and show the Independent that its editorial policy had customers.

So what can you do?

1. Read:

look at your own reading choices and any that you have influence over

(children, colleagues, students, family, customers…);

2. Buy:

if the industry thinks there isn’t a market, we have to show them

(give more diverse books as presents, at Christmas, as donations…);

3. Order:

If your local bookshop or library or school doesn’t have the (diverse) book you want, don’t just get it elsewhere, order it, demand they stock it (if it's a school, donate it)! (Otherwise they may never realise that there's a demand).

(The #WeNeedDiversBooks campaign in the USA asked all librarians attending the American Library Association conference to ask at every publisher’s display what diverse books they were offering);

4. Recommend:

(to friends, family, colleagues, in blogs, on Twitter…);

Did I say buy already? You can't expect other people to buy you book/publish books you like unless you buy them yourself. We authors can't eat tweets.

And you can start today, right here, right now.

My hero, Arthur Ashe has a phrase which I turn to when I feel defeated by the enormity of the task:,

Start where you are.

Use what you have.

Do what you can.

Each one of us has to start with what we can do

and if we all change one thing we can make a difference.

Thank you.

Works cited

Archer, John (1978) Biological explanations of sex-role stereotypes. In Jane Chetwynd and Oonagh Hartnett (ed) The Sex Role System. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (pp.4–17).

Bland, Lucy (1981) It’s only Human Nature?: Sociobiology and Sex Differences. Schooling & Culture, vol. 10 (pp.6–10).

Bookseller in association with Arts Council England and Decibel. In Full Colour. Bookseller, March 2004.

Bookseller. Books for All. Bookseller, June 2006.

Browne, Naima and Pauline France (1986) Untying the Apron Strings: Anti-Sexist Provision for the Under Fives (Gender and Education). Milton Keynes: The Open University Press.

Cadman, Eileen, Gail Chester and Agnes Pivot (1981) Rolling Our Own: Women as Printers, Publishers and Distributors (Minority Press Group Series No. 4). London: Minority Press.

Chester, Gail and Sigrid Nielsen (ed.) (1986) In Other Words: Writing as a Feminist (Explorations in Feminism). London: Hutchinson.

Fairweather, Hugh (1976) Sex differences in cognition. Cognition, vol. 4, no. 3 (pp.231–80).

Griffiths, Dorothy and Ester Saraga (1979) Sex differences and cognitive abilities: A sterile field of enquiry? In Oonagh Hartnett, Gill Boden and Mary Fuller (ed.) Sex Role Stereotyping. London: Tavistock (pp.7–45)

Klein, Gillian (1985) Reading into Racism: Bias in Children’s Literature and Learning Materials. London: Routledge.

Maccoby, Eleanor Emmons and Carol Nagy Jacklin (1974) The Psychology of Sex Differences. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Macken, Walter (1968) Flight of the Doves. London: Macmillan.

McQuinn, Anna (illus. Rosalind Beardshaw) (2006) Lulu Loves the Library. Slough: Alanna Books.

Radcliffe, Ann (ed. Bonamy Dobrée) ([1891] 1966) The Mysteries of Udolpho (Oxford World Classics). Oxford University Press.

Women in Publishing (1980?) Directory. London: Women in Publishing.

Working Group Against Racism in Children’s Resources (1983) Guidelines and Selected Titles: 100 Picture Books. London: WGARCR.

Afterward

(While this was a historical review of the ebb and flo of the advances and retreats in the battle to make children’s books more inclusive and diverse, my views on changing one thing are highly influenced by not just Arthur Ashe but also the Action Steps arising out of the CBC Diversity event

A Place at the Table in the US last year. As a publisher, I felt that if I knew that everyone who attended (and those to whom they spread the message) did their best to enact any of the steps, then I could be more confident of finding a market for my books. And I could hopefully also persuade any less confident publishers that change was in the air and that they too could be confident to take a risk in publishing something that wasn't the safe, lowest common denominator).

After afterward - the campaign described above went on to become the amazing #WeNeedDiverseBooks

* I rant so much I have a whole extra website for it here

RSS Feed

RSS Feed