Reflecting Reality and Representation –

What inspired me to produce inclusive literature -

This article commissioned by CLPE to co-incide with the publication of the second Reflecting Realities Report in 2018:

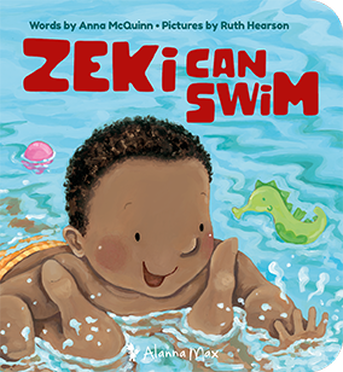

The CLPE’s latest Reflecting Realities survey, which examines ethnic representation in UK Children’s books published in 2018, features Zeki Gets a Check Up by Anna McQuinn and Ruth Hearson as an example of good practice when it comes to positive and sensitive BAME portrayals. As part of our Reflecting Realities blog series, author and publisher Anna McQuinn shares her background as a children’s author and publisher, and how her current work strives to make children’s books more inclusive in an intersectional way.

For me, I guess literature has always been political. Growing up in rural Ireland I didn’t always feel I ‘fit’. I never felt I was a ‘proper’ girl (though I was really lucky in having a bunch of other ‘not-girly-enough-girls’ as friends, so I wasn’t isolated).

Books were always my escape - I lost myself and found myself in stories. So it was a natural choice to read English at university.

Taking feminist criticism courses helped me understand that my discomfort at feeling not a proper girl (and more importantly my frustration at the narrow range of behaviour expected of me and options open to me) was simply a refusal to accept the narrow patriarchal role assigned to women and girls. Post graduation I studied Education and child development, specializing in Children’s Literature, and after teaching for a few years, I returned to UCC and completed an MA – a feminist reading of Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic Novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho.

I moved to the UK and tried desperately to get into feminist or academic publishing. It was my teaching experience that opened the door, however, and I got my first editorial job with an educational company. A Letterbox Library conference in 1990 was a turning point – I realized that little girls were as, if not more, than grown women in need of literature that honoured their whole selves and full potential. I decided then and there to move into children’s (trade) publishing – it would combine my two passions: feminism and social justice with child development and literacy.

Also on that day, in conversation with a member of the Working Group Against Racism in Children’s Resources, I was persuaded to join. Working with this group – first as a member of the Book Group and then as a member of the board for many years - enlarged my thinking on the influence of children’s literature on how children view themselves and others, and especially on what possibilities they can dream about.

I often quote from a piece that influenced me at this time - Caroline Halliday’s chapter: I tell my 3 year old she’s real… writing lesbian-feminist children’s books from In Other Words - Writing as a Feminist

The CLPE’s latest Reflecting Realities survey, which examines ethnic representation in UK Children’s books published in 2018, features Zeki Gets a Check Up by Anna McQuinn and Ruth Hearson as an example of good practice when it comes to positive and sensitive BAME portrayals. As part of our Reflecting Realities blog series, author and publisher Anna McQuinn shares her background as a children’s author and publisher, and how her current work strives to make children’s books more inclusive in an intersectional way.

For me, I guess literature has always been political. Growing up in rural Ireland I didn’t always feel I ‘fit’. I never felt I was a ‘proper’ girl (though I was really lucky in having a bunch of other ‘not-girly-enough-girls’ as friends, so I wasn’t isolated).

Books were always my escape - I lost myself and found myself in stories. So it was a natural choice to read English at university.

Taking feminist criticism courses helped me understand that my discomfort at feeling not a proper girl (and more importantly my frustration at the narrow range of behaviour expected of me and options open to me) was simply a refusal to accept the narrow patriarchal role assigned to women and girls. Post graduation I studied Education and child development, specializing in Children’s Literature, and after teaching for a few years, I returned to UCC and completed an MA – a feminist reading of Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic Novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho.

I moved to the UK and tried desperately to get into feminist or academic publishing. It was my teaching experience that opened the door, however, and I got my first editorial job with an educational company. A Letterbox Library conference in 1990 was a turning point – I realized that little girls were as, if not more, than grown women in need of literature that honoured their whole selves and full potential. I decided then and there to move into children’s (trade) publishing – it would combine my two passions: feminism and social justice with child development and literacy.

Also on that day, in conversation with a member of the Working Group Against Racism in Children’s Resources, I was persuaded to join. Working with this group – first as a member of the Book Group and then as a member of the board for many years - enlarged my thinking on the influence of children’s literature on how children view themselves and others, and especially on what possibilities they can dream about.

I often quote from a piece that influenced me at this time - Caroline Halliday’s chapter: I tell my 3 year old she’s real… writing lesbian-feminist children’s books from In Other Words - Writing as a Feminist

Reading a bedtime story is not as calm as it used to be. Not if you are a lesbian mother with a daughter who as a disability. A child needs to find her/his self, her likeness in the books she uses, not some patriarchal notion of the ‘normal’ child… |

I loved that she named the ‘stereotypes of physically perfect, white, middle-class children who live with mum and dad’ as a ‘patriarchal notion of what is normal’. Halliday also said

Feminist children’s books must show the multiracial society in this country, in which children and women live in different classes and are affected by race and class divisions. The books must explain how people live in different ways here and all over the world… |

This challenged my thinking. I regarded myself as someone whose feminist politics fed a desire for social justice and equality across class and race, but I had not given as much thought to the effect of stereotypical images on the development of young Black children as I had, for example, thought about their impact on young girls.

And so I read further on the subject, including Gillian Klein’s classic Reading Into Racism – bias in children’s literature and learning materials among others.

All of these influences led me to edit and later publish and write as inclusively as possible.

For me, inclusion has never been a ‘nice to have’ extra or a luxury, but an essential way of ensuring that as many children as possible see someone they recognize in their stories. I feel this is an absolutely fundamental right for all children and necessary to their development, their engagement with books, learning and reading.

It is also essential to their developing self-confidence, and their ability to imagine futures for themselves not limited by narrow gender or other roles:

We will only grow as big as we dream, that’s why we must dream big

– Gabrielle Williams

Any collection of children’s books which features a narrow range of representation sends a message that anyone who is not represented, or not represented well, is somehow not good enough. It can instill a false sense of importance or superiority in some children and deprives them of the full human experience and therefore opportunities for developing empathy. Representing a wide range of children benefits all children. It shows the world as it really is.

...political thinking is the touchstone for my writing and publishing.

But once I’m working on a story, I park it and focus on

making the best story possible.

This all sounds terribly dry and I’m not sure it’s terribly inspirational!

For me the political thinking is the touchstone for my writing and publishing. But once I’m working on a story, I park it and focus on making the best story possible. I switch focus from input to output.

One of the early decisions I made (not a little influenced by Verna Wilkins for whom I worked as a freelance editor for many years) was to ‘do’ inclusion in a natural and joyful way. There is a role for consciousness books that draw attention to identities positively.

However, as Rumaan Alam puts it, "Must every book featuring black faces force our children to confront the tortures of our past and the troubles of our present?" These are important, he adds, but

For me the political thinking is the touchstone for my writing and publishing. But once I’m working on a story, I park it and focus on making the best story possible. I switch focus from input to output.

One of the early decisions I made (not a little influenced by Verna Wilkins for whom I worked as a freelance editor for many years) was to ‘do’ inclusion in a natural and joyful way. There is a role for consciousness books that draw attention to identities positively.

However, as Rumaan Alam puts it, "Must every book featuring black faces force our children to confront the tortures of our past and the troubles of our present?" These are important, he adds, but

children must also learn the pleasure of reading a story in the relaxed, quiet moments before bed, reading not to learn but to feel safe, feel loved, laugh, wonder. That’s a fundamental privilege of childhood and should not be reserved for only one set of children.

I would add the question, why should any child only see themselves in books that deal with issues?

why should any child only see themselves in books that deal with issues?

Can you imagine being a little black girl and the only time you see someone like you in a book is when there is some issue to be resolved or adversity overcome? Mustn’t that just be so excruciatingly boring? And why should any child only see themselves in a book in order to teach other children about tolerance and acceptance? I suspect this one is because publishing itself is still so white, it still thinks of readers as white.

This is why, when I’m working on any book, I want to make a child who doesn’t usually get to be the hero into the star of the story – for no reason whatsoever. That is the point! No child should need a reason to be the star of the story. To quote Rumaan Alam again,

This is why, when I’m working on any book, I want to make a child who doesn’t usually get to be the hero into the star of the story – for no reason whatsoever. That is the point! No child should need a reason to be the star of the story. To quote Rumaan Alam again,

We need more books in which our kids are simply themselves, and in which that is enough.

And I imagine sitting in a pre-school or nursery and reading it with a group of kids who look just like the hero – something I was lucky to be able to do almost daily when I worked on a Sure Start project, running library groups for parents and toddlers.

The decision to more naturally include children who don't see themselves represented enough does have challenges – not least of which is how to market and sell such a title – a title that I’m really reluctant to label ‘diverse’.

I feel that a book can’t be diverse but a list or a collection can. And that what you call things does matter…

A book with a black child as the hero is only ‘diverse’ to a white publishing world. I’m happier with ‘inclusive’ – it speaks more to my passion to include everyone and for me, it’s a word that doesn’t centre whiteness in the same way. But then how to point to it? How to find it if you’re especially looking for a book with a black hero?

The decision to more naturally include children who don't see themselves represented enough does have challenges – not least of which is how to market and sell such a title – a title that I’m really reluctant to label ‘diverse’.

I feel that a book can’t be diverse but a list or a collection can. And that what you call things does matter…

A book with a black child as the hero is only ‘diverse’ to a white publishing world. I’m happier with ‘inclusive’ – it speaks more to my passion to include everyone and for me, it’s a word that doesn’t centre whiteness in the same way. But then how to point to it? How to find it if you’re especially looking for a book with a black hero?

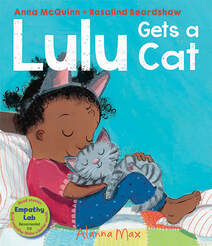

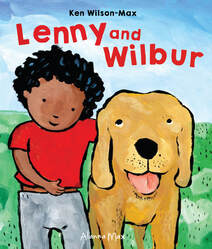

I am happy to describe my UK publishers, Alanna Max as a diverse (though I prefer inclusive).

They publish a diverse range of books that include a diverse range of heros.

And while they descrive the list as divers, they market each book as just what it is:

a story about a little girl going to the library; a story about a little boy and his dog; a story about a little boy learning to swim…

Which brings me right back to the beginning – that literature is political. I believe there’s no getting away from that. There are still publishers - and booksellers - around who argue that books for children are or should be somehow apolitical – as if shelves full of happy (read white, middle class, straight) families, along with miscellaneous bunnies, frogs, dogs and dinosaurs are not also making a political statement!

For me therefore, publishing inclusively is not so much making a political statement as making a political choice.

It’s a choice to make sure that stories for children reflect the realities of the lives they live; it's a choice to make sure that children see someone like themselves in stories (and especially in illustrations – early years is my passion after all!) And it's a choice to try to make these books as much fun/deeply moving/engaging – just brilliant – as they can be, so that every child will want to read them…

Reflecting the reality of multiple experiences and multiple narratives helps all children to open up to possibilities beyond their immediate circumstances. In this way, every child benefits from inclusive books – because everyone loves a good story…

I would like to acknowledge the input of Farrah Serroukh who commissioned the original piece. The improvements are all hers, the awkward bits I've left in are all mine.

The Reflecting Realities Report is here

The full Rumaan Alam article (one of my favourites) is here

Scott Wood Makes Lists - List of Black Picture Books that are not about Boycotts, Busses or Basketball is here

I've linked to the 2016 List as that has the original article. The updates in 2018 and 2019 are lists only.

I was really thrilled to see Lola Reads to Leo included in the original 2016 List (no 15)

#RepresentationMatters #ReflectingReality #ReadThe4%

This is not the first time I've written about 'natural inclusion' - for a slightly different take, you may like to read another article:

Who gets to hold the Purple Plastic Purse here.

They publish a diverse range of books that include a diverse range of heros.

And while they descrive the list as divers, they market each book as just what it is:

a story about a little girl going to the library; a story about a little boy and his dog; a story about a little boy learning to swim…

Which brings me right back to the beginning – that literature is political. I believe there’s no getting away from that. There are still publishers - and booksellers - around who argue that books for children are or should be somehow apolitical – as if shelves full of happy (read white, middle class, straight) families, along with miscellaneous bunnies, frogs, dogs and dinosaurs are not also making a political statement!

For me therefore, publishing inclusively is not so much making a political statement as making a political choice.

It’s a choice to make sure that stories for children reflect the realities of the lives they live; it's a choice to make sure that children see someone like themselves in stories (and especially in illustrations – early years is my passion after all!) And it's a choice to try to make these books as much fun/deeply moving/engaging – just brilliant – as they can be, so that every child will want to read them…

Reflecting the reality of multiple experiences and multiple narratives helps all children to open up to possibilities beyond their immediate circumstances. In this way, every child benefits from inclusive books – because everyone loves a good story…

I would like to acknowledge the input of Farrah Serroukh who commissioned the original piece. The improvements are all hers, the awkward bits I've left in are all mine.

The Reflecting Realities Report is here

The full Rumaan Alam article (one of my favourites) is here

Scott Wood Makes Lists - List of Black Picture Books that are not about Boycotts, Busses or Basketball is here

I've linked to the 2016 List as that has the original article. The updates in 2018 and 2019 are lists only.

I was really thrilled to see Lola Reads to Leo included in the original 2016 List (no 15)

#RepresentationMatters #ReflectingReality #ReadThe4%

This is not the first time I've written about 'natural inclusion' - for a slightly different take, you may like to read another article:

Who gets to hold the Purple Plastic Purse here.